Written by Heda Agić

Early days of fieldwork on the Digermul peninsula have yielded abundant fossils of macroscopic discs – attachment structures of large softbodied organisms such as Aspidella sp. that lived approximatelly 600-540 years ago. Such fossils are important since they represent some of the first visible records of complex life and the evolution of animals.

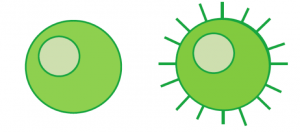

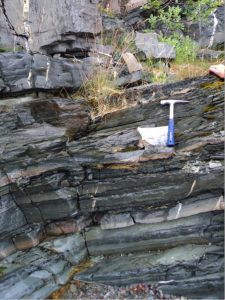

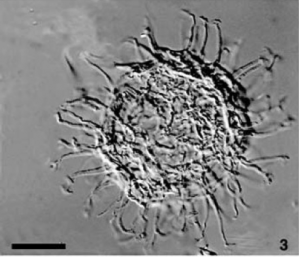

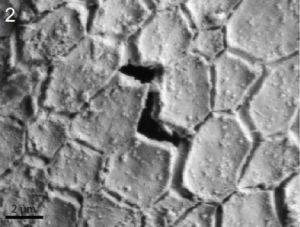

Yet the quest for the early life does not end with Ediacaran discs and other impressions visible to the naked eye. Even older fossils, and a great diversity of early Paleozoic ones, resides in the world of small, observable only with the aid of a microscope. Some of those fossils are minute, tenth of a milimeter in diameter, organic-walled, single-celled spheres called acritarchs (Figure 1). They are usually found along with clumped pieces of particulate organic matter and kerogen, in fine-grained, organic-rich shales. Most suitable rocks for acritarch preservation are usually olive green, dark blue or black in colour (Figure 2). These microfossils may also occur in chert nodules or more rarely, in limestones.

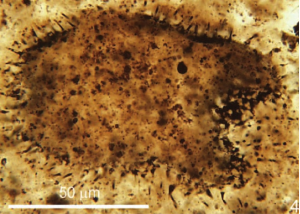

Acritarchs are prepared for microscopic observation by acid extraction from shales , clays, silts or limestones (using HF and HCl), whereby the rock matrix is dissolved and the individual carbonaceous fossils are picked carefully with a pipette and mounted onto glass preparates for light and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Rock chips containing the specimens (usually in case of cherts) may also be cut and polished into thin sections (30 µm thickness) and the fossils are observed in cross section (Figure 3).

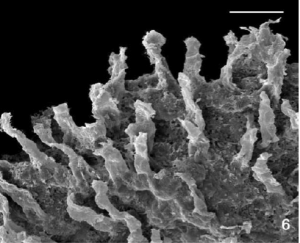

There is a lot of variation in size and shape among the acritarchs, but three main features of their body plan are shared: 1) resilient carbonaceous vesicle wall (Figures 4 & 5), able to withstand acid maceration; 2) processes (spiny protrusions) in different species (Figure 5); 3) round or split openings in the wall (Figure 4), called the excystment structure or a pylome. Processes were formed as the organism begun to develop a protective cyst, preparing for reproduction similar to modern algal zygotes, and these openings likely served for the release of gametes or daughter-cells as in many living protists.

Oldest acritarchs (leiosphaerids) are found in 1.8 billion year old rocks, while some other organic-walled fossils like bacterial sheaths and coccoids date as far back as 3.4 billion years.

Single-celled acritarchs are quite important for our understanding of the early life on Earth as they are the first record of complex and larger cells of Eukaryotes, a doman of organisms posessing a true nucleus (animals, plants, fungi, protists). By comparing ancient microfossils to modern microscopic marine organisms, it is possible to study the evolution and antiquity of different eukaryotic kingdoms.

Microfossils from the Proterozoic-Cambrian transition, such as those present on the Digermul peninsula, are particularly interesting for a better understanding of changing environments and biosphere revolution. As planktonic primary producers in the oceans, acritarchs would have depended on light and nutrient availability, so their diversity patterns through time may contribute additional information on the climate change in the late Neoproterozoic as well as the biotic turnover at the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary. They would have provided a significant food source for the rapidly evolving animal groups.

Being abundant, planktonic, usually globally distributed and with rapidly evolving form-species, acritarchs are excellent index (guide) fossils that can be used in correlation of Proterozoic and early Paleozoic rocks. If an acritrach species occurs worldwide and over a short time period, it may be used to identify different a stratigraphic units or a biozone. This is helpful in estimating the age of the rocks, especially where other dating methods are not available.