To record sounds is to put a frame around them.

Schafer (1973)

A yellow wagtail (Motacilla flava) has been following me. I have noticed it flying around me. The singing has become more intense as it has closed in on me. I hear the characteristic sharp, drawn out and high-pitched tune falling at the end – transcribed as “tsiiv, tsiiv”. Ornithology and identifying birds by tunes are part of my academic training. This is a bird that is easy to identify by the tune. The sound is regarded as primitive and not so striking. It has two or three notes resembling the contact in timbre. To me the sound is clear, clean and aesthetical beautiful.

At first, when I noticed the bird, it flew at a distance, but the oscillating pattern of its flying was recognisable to me as one of the wagtails. At a distance, I could not identify it by its feather coat. I thought it was the black and white feathered common wagtail (Motacilla flava), but I realised it was too even coloured to be that. The species systematics and phylogeny are messy and interestingly forming a cryptic species complex that does not fit with standard identification methods.

The bird lands in the bush in front of me. I move slowly towards it with the sound recorder. Now, I can see that its rump is olive and the breast yellow. It is a male, because females are greyer over the rump. The wagging tail is black and white and the white crown line above its eye ends at the root of his thin black beak. This is a beak for catching insects. I hope the sound of the wind does not destroy his specific singing. It’s a peaceful singing. A high-pitched tune – “tsiiv, tsiiv”. He is not afraid of me, but curious. He sits there like he has been watching me for much longer than I have noticed him. I am the visitor in his habitat. He probably has youngsters in the bushes that he wants to protect. I record several seconds of singing before he flies away.

5.1 Introduction

Why did I start the ethnography by describing the visual impression of my first meeting with the tundra? Even thought my aim is to do research on sound, all I have to say is that the wind rustles in the dry leaves and the bird sings with a high-pitched tune. This is where I start my performance turn in sensuous tourism research. Sound waves are floating around in the tundra and can be picked up by my ear and interpreted as tiny bits of information (Elert, 2019a; Farina, 2014; Feigen, 1971). I can learn how sound waves behave depending on the medium that contributes to the sound (Ingold, 2011) and the mediums through which it runs (Gjestland, 2018), the wind speed that enhances the speed of sound (Elert, 2019b) and all the other characteristics of sound will give me information about what I hear (Elert, 2019b; Gjestland, 2018; Henderson, 2017; Ramm, 2017). It is like learning to read – first letters, then words and sentences, and then context. What I will introduced here is just a little piece of the “alphabet” of sound and there is so much still to learn, to investigate and to research. I have picked out the things that would make a difference in describing the sound in the environment of the Finnmark tundra, at the lodge, amongst the visitors and in the surroundings of the hosting practices and the host.

In this chapter, I start by presenting the physical world of sound and how we hear. What are the characteristics of sound to which we need to attend and what is there to hear? I present and relate to the sonic definition of soundscape (Farina, 2014) in this context. I select significant sounds that I registered at Upper Mollešjohka Duottarstophu and categorise them into phonic groups, geo- bio- and anthrophonies of sources as presented by Farina (2014). Further, I discuss how some sounds are more prominent than others and what they tell us about the place in different contexts. I refer to the theories and thoughts in this chapter as the “hard” science of sound. I use the surroundings at Vuolit Mollešjohka and my experiences there to discuss some of the challenges of working with sound and I think about the information lost when not attending to sound in tourism. Based on this, I will try to answer the question:

- How can we learn about sounds that are present in a nature-based tourism destination?

5.2 The “hard” background science of sound

5.2.1 What is sound?

Electromagnetism is the field of study that relates to the physics of mechanical vibrations. These vibrations create waves of movement that differ in frequency and amplitude, how they are transmitted and absorbed within certain media and how materials are affected (Feigen, 1971). Different movements create mechanical pressure changes and spread like electromagnetic (EM) waves of energy flowing through the universe (Elert, 2019a). Roughly, lights and colours are visible to the human eye in the range between 430 and 751 THz (Gjestland, 2018). The higher the frequencies the longer the waves become (Elert, 2019a). The long wave low frequency part of the spectrum between 0 Hz and 20 MHz are referred to as sound. Hence, sound is the informative energy that participates in the physical phenomenon of pressure waves of a vibrating object (Farina, 2014). Mechanical vibrations create sounds in fluids by rapidly moving groups of molecules that have been compressed or expanded and rarified by the vibrating source (Feigen, 1971). Sound waves run through mediums such as air (gas), water (liquid) or wood and steel (solids) with different speed (Gjestland, 2018). Speed increases with higher temperature, atmospheric pressure and the speed of the wind (Elert, 2019b). When sound hits an obstacle speed will change and it will be reflected. As sound is waves, the hindrance will vary according to the size of the obstacle (Elert, 2019a). The materials in the medium, its surface and density, also affect how the waves are transported and reflected. Sound waves are a natural part of nature and are out there even if there are no living creature to sense them (Elert, 2019a; National Park Service, 2018).

5.2.2 How do we hear with our ears?

In humans, impressions of sound waves have primarily been related to the ears. The pressure waves of different frequencies create vibrating pressure in the cochlea and the semi-circular canals filled with a water-like fluid and over 20,000 hair-like nerve cells (Henderson, 2017). The nerve cells differ in length and have different degrees of resilience to the compressional wave in the fluid that sets them in motion. Each hair cell has a natural sensitivity to a particular frequency of vibration. When set, vibration increases in amplitude and the cells release an electrical impulse that passes along the auditory nerve towards the brain (Henderson, 2017). This is how sound is transduced to nerve impulses that are registered to the brain and perceived as sound (Pinch & Bijsterveld, 2012). Normally, the upper range of audible frequencies tends to fade with age and only kids and teenagers can hear sounds between 14-16,000 Hz (Feigen, 1971).

The amount of information to which a brain can attend is estimated to be about 120 bits per second (Levitin, 2014). A lot of irrelevant sound impressions are therefore sorted out and never processed in our brains. The attention span and filter protect us from being distracted by insignificant sounds in cases where attention must be paid to sounds that keep us safe and sound (Levitin, 2014).

5.2.3 The sonic characteristics of sounds

Sonic characteristics refer to the physical or conceptual artefacts created by sound (Farina, 2014). The brain analyses sound impressions from wave movements by their different qualities. In this thesis, I concentrate on the three most prominent characteristics of nature sounds, the frequency, amplitude and timbre (Gjestland, 2018; Ramm, 2017). This is because these are the easiest recognisable characteristics of sounds to people with no enhanced sonic skills.

The sensation of one or several waves of different frequency is referred to as a pitch (Gjestland, 2018). The pitch is perceived as high or low tunes. In the lower spectrum of audible frequencies, we find the bass, and in the upper the descant. People that are trained listeners may distinguish two tones that vary in frequencies of as little as 2 Hz (Henderson, 2017). Waves with frequencies that clash make dissonance and are noisy and unpleasant to which to listen. If several clashing frequencies are represented it, is called white noise and sounds like a waterfall (Ramm, 2017).

Loudness, or amplitude, describes the intensity of a sound and is measured in decibels (dB) (Ramm, 2017). This is perceived by our ears as the volume of the sound. The same sound will not be perceived to have the same loudness to all individuals (Henderson, 2017). Age is one of many factors that affects the ability to hear and perceive sounds. The Threshold of Hearing (TOH) is set at 0 dB (Henderson, 2017). Rustling of leaves has a volume of 10 dB and whispering 20 dB (Henderson, 2017). Mapping of nature sounds in national parks in the States shows that if humans where taken out of the picture, sounds in nature seldom exceeds 40 dB (National Park Service, 2018). Normal conversation lies in the area of 60 dB (Henderson, 2017). Amplitude also relates to how the sound behaves over time when it comes to duration, direction and distance. Direction can be perceived due to our ability to hear with two ears sitting on opposite sides of our heads. This gives an all surrounding ability to perceive sound, as with vision it is about 120o tract-like just straight in front of the eyes. Sound will reach the ears with a slight difference in time. This creates directional qualities of perceptions as left-right, high-low and front-back. The loudness of a sound can tell you something about the distance of its source – how near and far the source of a sound is from you.

Timbre describes the reason why an E on a piano sound different from the exact same E with the exact same volume on a guitar. There are multiple frequencies at play at the same time (Ramm, 2017). The material of the instrument that is played, as well as the temperature of the instrument, play a role in how the different waves of that tone behave. Some tones have a higher pitch, overtones, and some have lower, subtones. Over- and subtones together are known as harmonics and make the perceived change in quality of the sound, known as tone colour or timbre (Ramm, 2017).

5.2.4 What kind of sounds are found in the world?

The most enduring sources of sound are natural phenomena like weather, water and animals (Pinch & Bijsterveld, 2012). Interest in conceptualising what to hear has grown in the field of landscape ecology (Pijanowski, Farina, Gage, Dumyahn, & Krause, 2011; Pijanowski, Villanueva-Rivera, et al., 2011). There are many definitions attached to the concept of soundscape. In relation to the aim of this chapter, I find it fruitful to follow Farina’s (2014) description of soundscape; being the entire sonic energy produced by a landscape. It is the result of the overlap of three distinct sonic sources: geophonies, biophonies, and anthrophonies. The geophonies are the sounds that are produced by non-biological natural agents like the winds, the rivers, the rain, waves on a lake, thunder and avalanches. They represent a sonic background of which other sounds can mask, overlap or mix with and are affected by geomorphic traits, climate and weather. Sonic degradations are affected by ridges, mountains, and valleys. The pattern of the sound waves is affected by winds, humidity and temperature. These all contribute to local conditions of sounds in a specific region (Farina, 2014).

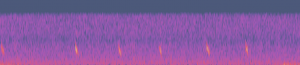

The biophonies are produced by living organisms in a specific biome (Farina, 2014). Ornithology is a field that for a long time has worked with the sounds of different birds (Bruyninckx, 2012). In order to describe the songs of birds, musical notation, graphic notations, nonsense syllables and phonetic vowels have been tried. These presentations have been rejected by conservative scientists due to the unscientific description of only the pitch and harmony and not considering timbre and other qualities of the sound. Recording using mechanical recording has not helped in a way that it was hoped. The ear is better at tuning in on specific sounds (Bruyninckx, 2012). Sounds are presented in scientific publications as writing or pictures (Pinch & Bijsterveld, 2012). Ornithologists that have developed significant sonic skills present the results as frequency (Bijsterveld, 2019b) or graphic spectrum charts. Only skilled practitioners can interpret the real results from the images (Figure 2). Despite challenges, ornithologists have developed considerable variations in knowledge about bird behaviour and how they are affected by changes in their environments. The possibilities of sharing video and sound through web pages makes it easier also to co-create knowledge about the variety of sounds from birds (Chernasky, 2019).

The graphic spectrum of “my” yellow wagtail’s song.

The graphic spectrum of “my” yellow wagtail’s song.

Acoustic complexity of biophonies are high because of intra- and interspecific individuality in active and passive communication and movement. Despite technological development, it is not always possible to identify all biophonies that compose a soundscape (Farina, 2014). Krause (2012) excludes human-made sounds from this category and calls them noise. Farina (2014) thinks the human voice should be considered and included but does not mention other natural sounds of humans. Biophonies have different patterns related to season, hours of day and latitude. Of course, fish makes sounds in the water, but these sounds are not accessible to humans except by using specific technology like hydrophones (Farina, 2014).

Anthrophonies are produced by artificial devices made by humans (Farina, 2014). They are increasingly regarded as intrusive and dominant parts of soundscapes (Dumyahn & Pijanowski, 2011; Farina, 2014; Krause, 2012; Qiu, Zhang, & Zheng, 2018). Anthrophonies are associated with urban development and globalised trade (Farina, 2014). As a major cause of noise pollution (Krause, 2012), anthrophonies can cause dangerous consequences to all organisms and to human health (Farina, 2014). Exposure to noise increases in importance when moving towards urban, industrial and transportation areas. The different phonies interrelate. Geophonies are the least affected along a gradient from intact natural landscape to rural and urban landscapes. In contrast, as anthrophonies increase with increased human intrusion, biophonies are very much affected and decrease accordingly (Farina, 2014). The spatial overlap of geophonic, biophonic, and anthrophonic patterns creates soundscapes (Farina, 2014). Soundscape ecology has important applications in the assessment of the environmental quality of parks and protected areas, in urban planning and design, in ethology and in anthropology, and finally in long-term monitoring.

Every phase of matter and every type of material reacts differently to sound waves (vibration), and this can be useful for remote sensing procedures to monitoring the dynamics of environmental context and behaviour of individuals (Farina, 2014). Ingold (2011) calls for more attention to materials and their properties. As mentioned above, the material is important to how soundwaves behave, reflect and are shaped, formed and moved (Feigen, 1971; Gjestland, 2018; Henderson, 2017; Ramm, 2017). The medium, composition of mediums and surfaces of the source or the space between the source and the perceiver play an important role in how the characteristics are perceived. The harder the material the fewer frequencies, the longer the waves are carried and the clearer the timbre. Like when you use a metal tuning fork or a brass instrument. The softer the material the more silent and thump the sound becomes. Like wool where sound is not carried through the material and the sound is silenced instead. Wood is semi-hard. Depending on type of wood, the different hardnesses of wood bring sound forward with different characteristics, for example, in acoustic wooden pianos and guitars. In nature, there are different materials too, like trees and water, grass and sand. Sand and grass do not carry sound very far (Farina, 2014), but water does (Feigen, 1971) like when in a fog.

5.3 “Hard” analyses of hearing and sounds at Vuolit Mollešjohka

In the surroundings of Vuolit Mollešjohka Duottarstophu, complete silence is rare. At the same time, it was easy to find places silent enough to catch the very quiet sounds of nature. The rustling of leaves sometimes sounded very high in almost no wind because of the absence of other sounds interfering. When there is less variety and loudness of sounds, the attention can include very low sounds that would otherwise be excluded from our attention spans (Levitin, 2014). It makes it possible to pay attention to the “little” things in the world. Upon my arrival, I started out making a list of what I could hear and found that I could constantly add new sounds to the list. Mapping sounds and trying to document significant sounds was first a methodical challenge. The soundscape was not fixed in time and place. Sounds travel along with moving sources. Like people and vehicles passing the place or game running and flying away. So, there are some anthrophonic sounds that are sometimes there and sometimes not. The presence is unpredictable and there is no sort of rhythm to which to relate, at least not in the short term. My own movement regarding the sources also changed and contributed to making sounds and continuously created new ones as I moved. This movement was sometimes rhythmical sometimes not. Most of all, it frequently appeared as an unwanted interference with my aims of recording.

The tundra is almost flat and has few sound barriers for sounds emanating from sources high up in the terrain. Sound sources low in the terrain were blocked by the ridges, but the rivers could carry sound along them as through channels. Noise from the waterfall south of the lodge was louder closer to the riversides even if the distance to it was greater than to the top of the ridge. Recording soundscapes gave me another chance to listen to what there was to hear and gave me new information every time I listened to the recordings. This was especially the case, when listening to the sounds of the different rivers and streams, and also in the case of river boats going up and down the river. The body of water in the tundra is enormous. Rivers and lakes run like arteries and veins through the landscape and in the middle is that heart – the great Iešjávri. The flow of the aorta, Iešjohka, runs out from it, into the watercourses of the Deatnu river before it enters the ocean. The mires and ridges are muscles and bones, the birch forest are the lungs that produces oxygen and use carbon-dioxide and the heater is the skin that protects the landscape and keeps it moist. The tundra is alive and the life sustaining process of water circulating in the world can be sensed particularly at this place. You cannot be closer to the living planet than by the rivers and right there where you can sit down and hear it.

I tried to categorise the sounds according Farina’s (2014) classification. The majority of biophonies on the arctic tundra are produced by birds and insects, mammals give sounds mostly during breeding seasons and when encountered by humans. Sounds from amphibians are rare and produced almost entirely by frogs. The seasonal effect is higher in boreal and arctic latitudes than in southern latitudes due to the higher variance in weather, light and temperature (Farina, 2014). I found that some of the sounds were not that easy to classify. The first sounds I noticed was the sound of my boots and the wagon in the sand and how we hit the big rocks. I found it hard to categorise these sounds as geophonic, biophonic or anthrophonic. Is it the boot or wagon that make the sound? Or is it the rock or sand? Or, is it me inside the boot and dragging the wagon hitting the rock and sand? Maybe it is the connection of me, the technologies and the environment? I think of them as intermediate phonies between geophonies (the rock and sand), biophonies (me and my foot) and anthrophonies (the boot and the wagon). Performances make the key sounds harder to detect, distinguish and categorise. They are often a cooperation between living creatures, technology and the surroundings. Then, I started to think about Farina (2014), who considers human speaking as a biophonic sound even though it is made by humans. I could not decide how to make a distinction between biophonic and anthrophonic sounds. All bodily sounds made by humans are not made by intention like talking is. So, if talking is a biophonic sound, so are the bodily made sounds. Then what are the anthropic sounds? Are they sounds from industrial devices? What is industrially made sounds? Are sounds from tools that animals like crows and magpies manufacture (Shumaker, Walkup, & Beck, 2011) biophonies or anthrophonies? These questions are not so easy to answer. Bringing them up in this context generated an argument that set me on my way to tear down the walls between humans and nature. Even though these categories make sense, and they can easily be used as analytic tools or categories to try to sort out complexity, there are more to sounds than can easily be sorted out by just using the ears. By using the ears, it was of course possible to describe what sorts of sounds that were there, and which were not, and, as a reflexive exercise, to try to put them into Farina’s (2014) categories.

Situated far away from urban environments, traffic noise was not common, and cars could be individually recognised by sound after a few days. People talked together with low voices and could sit on the benches outside in silence. A few Finnish guys talked quietly in Finnish and only made noise by slamming the hanging old wooden doors of their cabin and the sauna. Most of the anthrophonic sounds were situated indoor. Like Farina (2014), I too considered most of them biophonies. The sound of different languages, dialects, speed of words, loudness of the voices and laughter are certainly important in a tourism space as they say something about the guests and culture being present. Different languages have their own tune and that has certainly something to do with how you feel connected to a place in tourism. A Sámi tourism business does not feel the same without people speaking Sámi, as France doesn’t feel French without listening to people speaking French – even though you do not understand a word of what they are saying.

The first thing I noticed in my fieldwork notes was that I had used a “harder” scientific description of the flora and fauna in the place – describing them also with the correct species identifications in Latin. I am a biologist – this is what matters to me when describing a walk on the tundra and how I learn to know the environment I am visiting. I notice all the other species situated there – with me. To me, all the other living creatures are individuals and just as important to the earth as humans. The second challenge I found while writing out my ethnography was that describing the sounds as I heard them was close to impossible. I tried to describe the sound of the rustling leaves, but I had no idea how to do that. I read other scientists attempt to describe sounds (Nuckolls, 1996) and investigated ornithologic discussions on sound (Bruyninckx, 2012). Still it was no easy task and did not quite resemble my experience with the sounds. Going back to my first piece of ethnography presented at the beginning of this chapter, I tried to describe the bird’s song by adding the notion “tsiiv, tsiiv”. This is how I have learned to transcribe the song of a yellow wagtail in Norwegian. A quick search on the internet tells me that in English the song is transcribed as “pseeeoo”. To me that is a completely different sound. I use this example to shows the difficulties of transcribing any sounds of nature as phonetics differ with the experience and skills of the ear of the listener. They are therefore not that easy to translate between different languages, disciplines and people. This might be one of the reasons why birdwatching tourists and ornithologist have come together to gather bird sounds upon common web pages (Chernasky, 2019). The next thing I noticed in my field notes was that I was really taken with some specific sounds, like the sounds of moving water and blowing wind, the singing birds, the rustling leaves and the noise that I made. There were certainly other sounds to which to attend, but to cope with the impression, I blocked them out. Sounds that were very present were, for instance, the pinging musical chord sounding every time I turned on the recorder, the four wheelers with reindeer herders driving past, Siri’s sheep and dogs, and the guests at the lodge. I realised that I had unconsciously used a political approach in my first review of the soundscape (Jensen, 2016). Painted by the typical duality of inclusion/exclusion of sound in nature and tourism management, I kept to simple questions like: What can be heard? What cannot? How is the silence outdoors affected by the sound of tourists? How can sound be used to support Sámi tourism? With a political approach, I left them all out in favour of looking at valuable sounds in accordance to possible impacts or noise. In a traditional natural science context, I could have used this mapping and the knowledge I initially gained to create a map of different impacts from anthrophonic sounds (National Park Service, 2018). I could have argued in a management context preventing mass tourism at the place because it would disturb wildlife. I could also argue against establishing windmills in the environment, because sonic qualities for tourists seeking silence would be destroyed by the sound of the mills. Attention towards specific sound could mask others making significant sounds unnoticed (Levitin, 2014). I would not have known this unless I had recorded it and listened to it several times afterwards. The more tired I was, the worse my attention, and more sounds were left out. Sometimes I had problems picking up on what people said because I was tired and even though my ears heard people talking, I could not hear what they said. The attention span was narrowed by the overall mental capacity.

I have used this chapter to present a gateway into the field of soundscapes. The Finnmark tundra is certainly alive and constantly moving. This is also true for every place visited by tourists, as tourists themselves add sounds to a place. A symphony is continuously made and re-made by the sounds of movements. All the parts move in different ways, at different distances, towards different places, at different speeds and at different times – and all parts create sounds audible to humans or not. The basis to understand this, is made up of “hard” theories about sound and hearing in relation to my visual and acoustic experiences on the tundra. I have argued that sound has possibilities to give us information about the environment in which we find ourselves at any given time and place. To be better abled we can develop our sonic skills, a few characters of the basis have been described above. To talk about skills, we need to add a body to the mind and the ear. In the following chapter, we need to start to listen to learn about the different soundscapes of guests visiting and the people living and caring for the land- and soundscapes.